The episodic film “GG19”, supervised by Harald Siebler, deals with the first 19 articles of the “Basic Law”, the constitution of the Federal Republic of Germany. Each episode was filmed in a different city in Germany, including Berlin, Görlitz, Regensburg or Karlsruhe. The cinematic experiment consists of contributions by 25 screenwriters, 19 directors, and well-known actors and actresses in front of the camera, including Anna Thalbach, Katharina Wackernagel, Anna Loos and Kurt Kromer. The film by Movie Members Filmproduktion was made as a co-production with BR-alpha, SWR, WDR and ZDF.

The episode “The Big Con” deals with the subject of censorship. Article 5 of the “Basic Law” enshrines the right to freedom of expression, which is repeatedly referred to in the court hearing in this episode, particularly by the accused. It reads: “Every person shall have the right to freely express and disseminate his opinions in speech, writing and pictures and to inform himself without hindrance from generally accessible sources. Freedom of the press and freedom of reporting by means of broadcasts and films shall be guaranteed. There shall be no censorship.”

The story takes place in a courtroom. On trial is the TV reporter Manfred Botz, who is accused by the public prosecutor of having falsified his reports with fraudulent intent. Botz, on the other hand, invokes freedom of expression and affirms that his reports were based on facts. Right here, the episode reveals the tension between lies and truth that could not be more up-to-date, as the system of the media has changed even further and detrimentally since the filming of this production in 2007. Fake news is being misused for populist purposes, even in politics, by the most powerful in the world. Think, for example, of the ex-US President Donald Trump or the Russian President Vladimir Putin, who have their own versions of the truth.

Additional examples include the German Querdenker movement (lateral thinkers), Covid-19 deniers and QAnon supporters, all of whom bring the most incredible conspiracy narratives to the public.

What the TV reporter Botz did to increase audience ratings is only a comparatively harmless harbinger of what happened in the mass media in the following years and which has reached unprecedented heights of harm today in terms of fake news.

That his “news reports” are very real developments is Botz’ defense argument, while the courts position is that the sale of fantasy stories is unethical and therefore fraudulent. Botz counters, that the judge, lawmakers and prosecutors have no idea how journalism works. That in fact “all news is actually staged”, sounds plausible, coming from such a confident, persuasive and handsome accused. Botz , who defends himself claims that it were his “ staged television pictures on November 9, 1989, showing people crossing the border that had mobilized the masses and led to the opening of the Berlin Wall that same evening. This was true journalism, (he added) that was closer than reality itself”.

The fact that he is now also producing multi-million dollar PR campaigns, on behalf of unnamed employers to make the welfare state “leaner”, backed up with false statistics in order to completely change the climate of public opinion, is all the more oppressive since these elements of the story are based on real facts, as the director explains in the credits of her director’s cut: “The trial was re-enacted – based on video recordings that were passed anonymously to the director.” Nina Franoszek emphasizes this aspect of the staging again in her interview (Conversation with Nina Franoszek, Page 110)

The female journalist, who sits as a spectator in the courtroom, plays a particularly important role in the story. She has previously put on a pair of glasses with a hidden camera in the restroom to (illegally) record the trial. The fact that the defendant Botz knows her, that the two of them are probably in cahoots, can be seen through furtive exchanges of glances between the two.

Here, the episode of the feature-length version and the director’s cut, which has the title “Meinungsmacher” (Spin Doctor), differ in one essential point. In the feature-length film, as the judge clears the courtroom, because the gallery had gotten unruly, the female journalist leaves to tell an unidentified person that the video recording didn’t work and throws the videotape into a trash can.

In the director’s cut, there’s this one brief moment in the courtroom when, in the commotion, Botz beckons her over and asks: ‘Give me the glasses!” to keep on recording. But she doesn’t comply, instead she leaves the courtroom. In the subsequent phone call with an editor-in-chief we find out that she refuses to participate in this kind of journalism. Here she demonstrates a professional ethic that the defendant has completely lost and the episode continues to raise important thought provoking questions that inspire viewers to reflect on the subject of: How far can journalism go and are there limits despite the freedom of expression enshrined in the Basic Law?

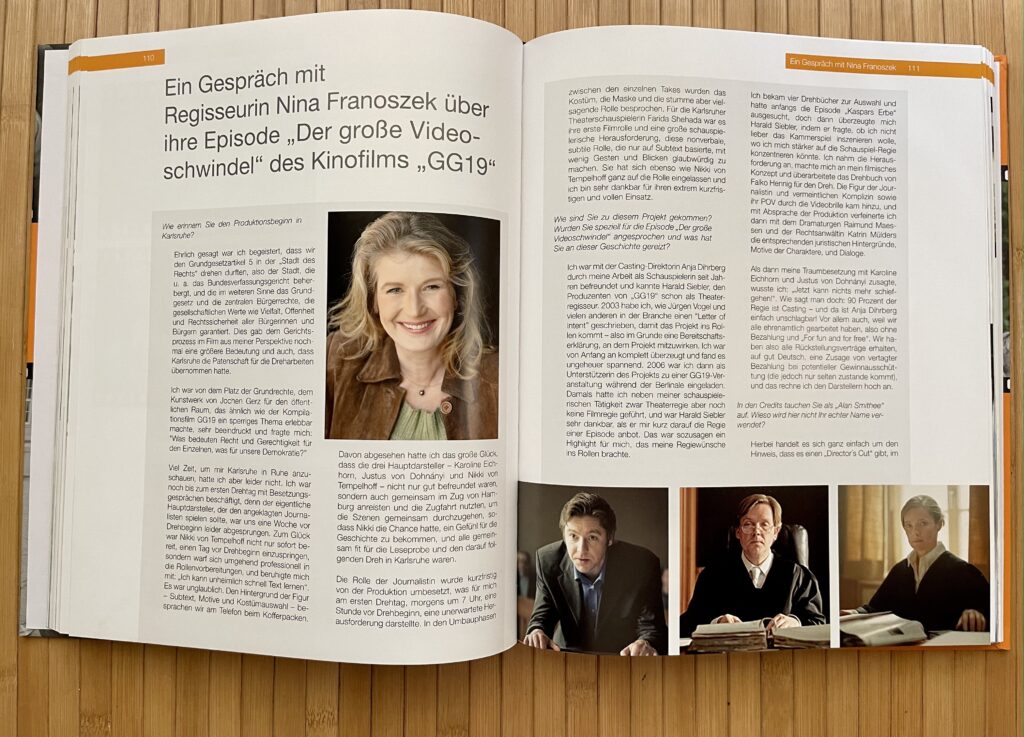

A conversation with director Nina Franoszek about her episode “The Big Con” from the compilation movie “GG19”

How do you remember the start of production in Karlsruhe?

To be honest, I was thrilled that we were allowed to shoot Article 5 of the Basic Law in the “City of Law”, the city that hosts, among other things, the Federal Constitutional Court and in a broader sense guarantees the Basic Law, the central civil rights and social values such as diversity, openness and legal certainty for all citizens. From my perspective, it gave the court case in the film even greater importance and also the fact that Karlsruhe had taken on sponsorship for this episode’s film production, made us all very grateful.

I was very impressed by the “Platz der Grundrechte” (Square Of The Basic Law), Jochen Gerz’s work of art for public space, which, like the compilation film GG19, made a stiff subject come alive and I asked myself: “What do law and justice mean for the individual and for our democracy ?”

Unfortunately, I didn’t have much time for sight seeing in Karlsruhe. I was busy with casting decisions and meeting actors until the first day of shooting, because the actual lead actor, who was supposed to play the accused journalist, had unfortunately dropped out a week before shooting began.

Luckily Nikki von Tempelhoff was ready to jump in one day before the start of shooting. He immediately threw himself into preparations for the role and reassured me by saying: “I can learn text incredibly quickly”. It was amazing. We discussed the background of the character, subtext, motivation and costume selection on the phone while each of us were packing our suitcases.

Besides that, I was very lucky that the three lead actors Karoline Eichhorn, Justus von Dohnányi and Nikki von Tempelhoff, were not only good friends, but also traveled together from Hamburg and used the train ride to go through the scenes together, so that Nikki had the chance to get a feel for the story, and everybody was well prepared for the table read, as well as the subsequent shoot in Karlsruhe.

At 7 am, on the first day of production, an hour before shooting started, the role of the video recording journalist was recast at short notice, by the producer, presenting an unexpected challenge for me. Costume and make up for this silent but meaningful role were discussed during set ups and in between individual takes. The Karlsruhe stage actress Farida Shehada, who was just cast and debuting her first film role, faced the particularly difficult acting challenge of making this non-verbal, subtle role, based on only subtext, credible with a few gestures and glances. Like Nikki von Tempelhoff, she completely got fully immersed in the role and I am very grateful for her extremely short-term and full commitment.

How did you come by this project? Were you approached specifically for the episode “The Big Con” and what attracted you to this story?

I had been friends with casting director Anja Dihrberg for years because of my work as an actor and I knew Harald Siebler, the producer of “GG19”, as a theater director. In 2003, I, like Jürgen Vogel and many others in the industry, wrote a “Letter of Intent” to get the project rolling – basically a declaration of willingness to participate in the project. I was a firm believer from the get-go and found it incredibly exciting. In 2006 I was invited to a GG19 event during the Berlinale as a supporter of the project. At that time, in addition to my acting, I had directed theater but not yet directed a film, and I was very grateful to Harald Siebler when he offered me to direct an episode shortly afterwards. That was, so to speak, the highlight that launched my film directing career.

I was given four scripts to choose from and initially chose the episode “Kaspar’s Legacy”, but then Harald Siebler convinced me to direct the intimate court room drama, where I could concentrate more on working with the actors. I accepted the challenge, started working on my cinematic concept and revised Falko Hennig’s movie script for the shoot. Upon agreement with production I added the character of the female journalist and alleged accomplice, as well as her POV through the video glasses. Script consultant Raimund Maessen and lawyer Katrin Mülders helped me to refine the corresponding legal backgrounds, motifs of the characters, and dialogues.

When my dream cast, Karoline Eichhorn and Justus von Dohnányi, accepted the roles, I knew: “Nothing can go wrong now!”, because as the saying goes, “Directing is 90% casting” and casting director Anja Dihrberg was simply unbeatable! Above all, because we all worked on a voluntary basis we accepted deferral contracts. In plain English, this is an agreement to defer all of our pay until the production has the money to pay us with potential distribution of profits (which, however, rarely happens), and as we all knew, “this was just for fun and for free”, I gave the renown cast great credit for participating.

In the credits you appear as “Alan Smithee”. Why is your real name not used here?

This is an indication that there is a “Director’s Cut”, in contrast to the “Producer’s Cut” that was used in the compilation film.

I had supported the project because I loved the idea for artists, writers, actors and directors to discuss and engage artistically with the Basic Law, and for everyone to be able to choose their own version, genre and style.

In the end, however, it was certainly not easy for the producer to bring the very different film styles into an overall framework, after all it was his debut as a film producer. For this purpose, director cuts were changed and the various episodes were combined with the music of FM Einheit, which legally was a tightrope walk – which we were able to solve to everyone’s satisfaction in cooperation with the Directors Guild and the producer.

In any case, my “Directors Cut” did not end up in the compilation film, therefore I identified the “production cut” with the official pseudonym “Alan Smithee” at the time. This is basically the hint for film insiders that there is also a “Director’s Cut” that was then screened in Los Angeles at the Goethe Institute.

What do you have to pay attention to when you are responsible for an episode of a movie that has to fit into the overall film?

Apart from the given length of exactly seven minutes, each director was completely free to express his/her artistic vision. However, it was important from the start that each episode had its own style reflecting the individual directors. During this time there were many other compilation films such as “Paris, je t’aime”, where it was known that this is now the Tom Tykwer part and this is the episode of Gus van Sant or of Gérard Depardieu. In this format the audience looks forward to the interpretation of each director, even if they are not well-known.

What was it about this episode that attracted you overall and how did you implement your vision?

My episode is about freedom of expression, if you will, which I personally had been concerned with for a long time. What’s happening today and what you see on Fox News, for example, is a manipulation of opinion that produces fake news under the guise of freedom of the press.

At the time we made this film, there was a scandal with a large-scale neo-liberal campaign “The Initiative for a New Social-Market Economy (INSM)” founded and funded by the metal industry employers’ association in 2000 to shape public opinion and policymaking, which was actually campaigning for unemployment and social benefits to be abolished, tuition fees to be introduced for traditionally free college education and taxes to be reduced for employers.

As it turned out, they surreptitiously paid to have the scripts and dialogues of actors changed in Germany’s most popular daily soap opera, Marienhof, to positively represent the dogma of the INSM, fully intending to manipulate the opinion of the audience. This was very explosive for me at the time and I worked it into the script.

Initially the arguments of the accused seem plausible in my film, he seduces us, until we learn from the prosecutor how manipulative and dangerous he is, and that in fact, he was also the one who was placing the false reports on behalf of the INSM. The female journalist who illegally films the court hearing for him through video glasses, realizes from the statements of the public prosecutor, what she has become involved with and then decides not to go along with it.

During the filming, as a big fan of Sidney Lumet, I kept thinking of his feature film “12 Angry Men”. However, for me it was not about the group dynamic of jurors in the US courts, but about the personal responsibility and civil courage of the individual. In this case, the female journalist decides, during the hearing, not to contribute to the fake news and a manipulation of the facts, but to destroy the material she recorded.

The film was shot in the district court of Karlsruhe-Durlach. How was the hall redesigned for the film? In the original state it looks a little different …

Yes. That’s correct. Interesting that you ask about it. Albrecht Silberberger, the cinematographer, was already there in Karlsruhe, had seen the location and sent me the photos. When I saw this white courtroom, it was too sterile for my aesthetic vision for the film, and I asked that it be painted. That was done and it looked great. The city authorities looked at it in disbelief and asked: “Why did you paint the courtroom so dark?” I reassured them, “it condenses the atmosphere in the film, makes the tension more dramatic and the actors expressions more pronounced”. It worked perfectly and I love the light that Albrecht created to this day. It was a great collaboration.

How many days of filming were available for the episode on location in Karlsruhe?

We only had three shooting days for the film that included a short guerrilla shoot (without permits and a bare-minimum crew) to round off the scene of the journalist’s departure with images of a gate nearby which, thanks to Albrecht Silberberger’s lighting, looked like the entrance to the court even though it was actually a drive-through. And then we had to quickly relocate up to the Turmberg castle and film our pan shot over Karlsruhe before sunset. Filming remained exciting until the last shot was in the can.

Another challenge was the filming of the video clip with the immigrants and right-wing extremists in the courtroom, since I hadn’t another shooting day, but preferred a video clip over photos as evidence. I remembered that my friend Dani Levi had shot a scene like that in the anti-fascism compilation film, “Germany in Autumn” (episode “Without Me”) on which we had worked together, among other films. He was so kind to make the video clip with the right-wing extremists, that is shown during the trial, available to me. It was a wonderful gift from another director, and I am grateful to him for it to this day.

The episode is about the right to freedom of expression, which was very much discussed last year in light of the many fake news reports that were spreading via some media. The episode was almost prophetic in terms of the development of the reporting … Yes, exactly! Maybe also because I was living in the USA at the time. The Swiss star journalist Tom Kummer had just been exposed as a purveyor of fake news causing one of the biggest media scandals in Germany. It turned out that his interviews with well-known celebrities were largely fabricated, and his lack of insight on the theory of “redefining reality” made him a perfect model for the role of the defendant Manfred Botz’s alter-ego.

The original script written by Falko Henning was inspired by the journalist Michael Born, who in his “fake news” showed alleged child slaves in India knotting carpets for IKEA, staged a Ku Klux Klan meeting with friends in the German Eifel for which his mother had sewed the robes and many other falsified documentaries. Born justified himself by saying that at the beginning, the focus was not on the fun of counterfeiting, but on concern for one’s own safety and journalistic zeal. After four years in prison, however, the media landscape had changed so much that he no longer understood why he had actually been convicted.

I believe that conspiracy narratives or alternative facts generally bring good ratings, especially because traumatized people want to hold on to something when they are afraid or very insecure. You are then the one who already knows everything or who already has access to the truth, which gives you the feeling of control, or a scapegoat for the respective situation. This in turn protects against having to face reality, one’s own helplessness and loss of control. But life is of course much more complex. We all are limited in our understanding. We all have fears or are directly impacted by the events around us and always have more questions than answers. It was important to me back then to question this and raise awareness. That was, so to speak, and still is today, one of my passions.